An exhibition where the pen, writing, and letters have “found their voice”!

In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, writing in Central Asia was not merely a means of documentation but evolved into an art that expressed spirituality and intellect. At the tip of the pen lay knowledge, in the ink spiritual depth, and within the letters an entire civilization. The calligraphic exhibits from this period displayed at the Islamic Civilization Center in Uzbekistan testify to the refined intellect and artistic taste of our ancestors.

In the second half of the fourteenth century and throughout the fifteenth century, Central Asia particularly the regions of Mawarannahr and Khurasan witnessed remarkable progress not only in science, literature, and architecture, but also in the art of calligraphy. Writing ceased to be a simple tool of communication and became a sophisticated art form reflecting intellectual creativity, aesthetic sensibility, and spiritual maturity.

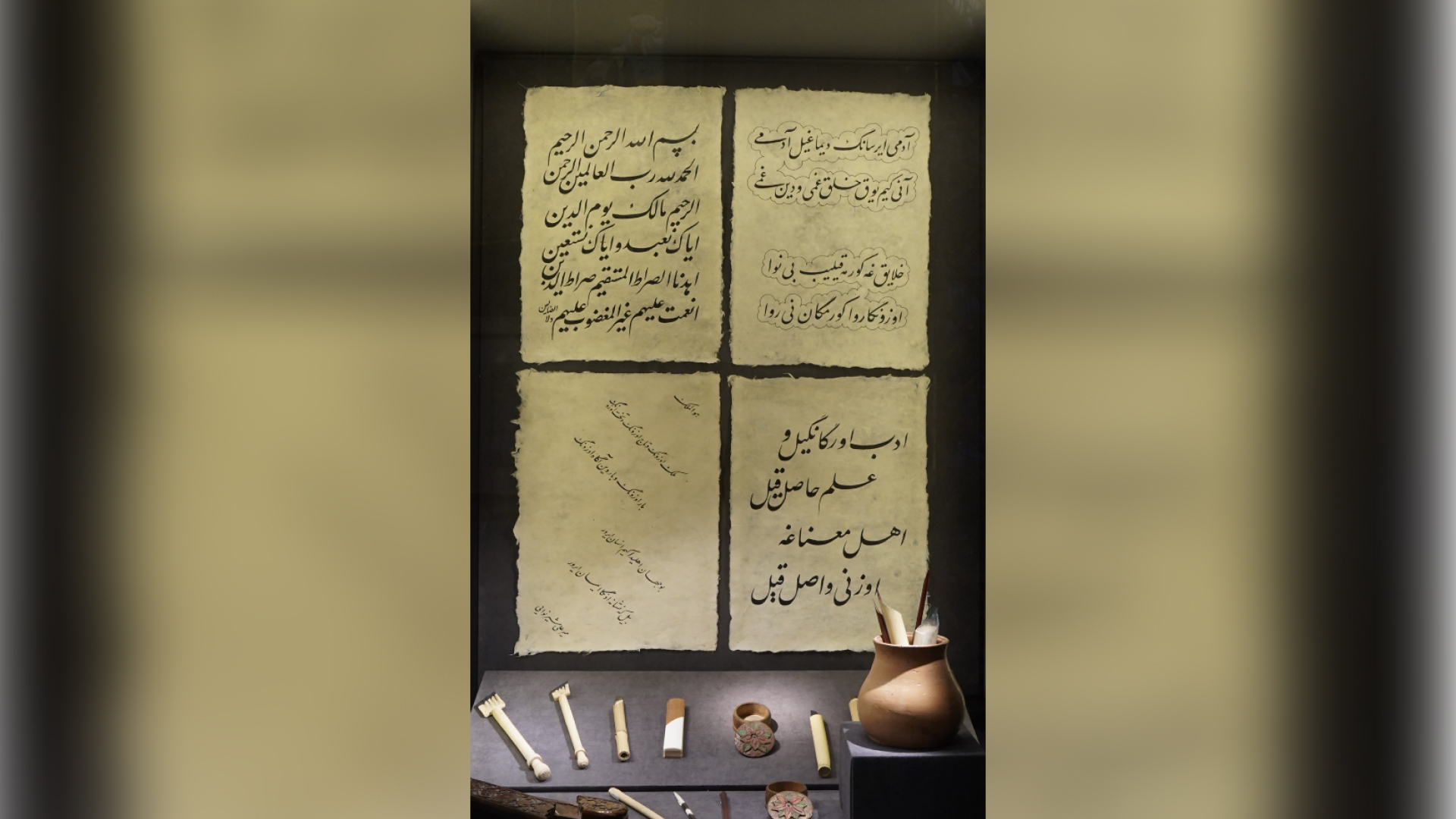

Calligraphers produced copies of the Qur’an, collections of hadith, and scholarly and historical works with exceptional mastery, not only in content but also in form and style. Scripts such as naskh, thuluth, muhaqqaq, and nasta‘liq were refined, calligraphic schools emerged, and their traditions were preserved over centuries.

Calligraphic objects displayed on the “Wall of Civilizations and Discoveries”

Specialized tools played a crucial role in the development of calligraphy. Pens, pen cases, and inkstands served not only practical needs but also embodied the aesthetic views, craftsmanship, and spiritual worldview of the era. Pens made from reed, bamboo, or pomegranate branches were carefully prepared to suit each script style. In the hands of a calligrapher, the pen was revered as a delicate instrument that transferred thought and spirituality onto paper.

Pen cases, crafted from wood, metal, or ceramic and adorned with ornamentation and inscriptions, reflected the calligrapher’s social standing and artistic taste. Inkstands were used to store ink and preserve its quality; the durability of inks prepared according to special recipes depended largely on these vessels.

The inclusion of verses from Surah al-Fatiha in the exhibition carries symbolic significance. In Islamic culture, al-Fatiha is regarded as a prayer of mercy, guidance, and spiritual direction. For this reason, it is interpreted as a spiritual preface to the civilizational ideals that call for knowledge and enlightenment.

“The calligraphic art of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries is a vivid expression of the development of Central Asian civilization, reflecting the harmony of science, spirituality, and art. The exhibits displayed on the ‘Wall of Civilizations and Discoveries’ serve as an important bridge conveying the scholarly heritage and artistic thought of our great ancestors to the present generation,” says Habibulloh Solih, senior research fellow and calligrapher at the Islamic Civilization Center in Uzbekistan.

The texts presented in the exhibition also carry profound spiritual meaning. In particular, the famous lines by Alisher Navoi on humanism, justice, and moral responsibility are presented as a symbol expressing the core values of civilization:

If you are human, do not merely claim the name of man;

He who has no concern for the people’s pain is no human.

These lines emphasize that human worth is measured by one’s responsibility toward society. Likewise, verses about justice, fairness, and faith reveal the inseparable connection between knowledge and spirituality in Islamic civilization.

Today, these calligraphic exhibits hold a worthy place in the “Wall of Civilizations and Discoveries” exhibition at the Islamic Civilization Center in Uzbekistan.

Durdona Rasulova

P/S: The article may be republished with a link to the Center’s official website

Most read

Over 100 experts from more than 20 countries of the world are in Tashkent!

President of Serbia Aleksandar Vučić visited the Islamic Civilization Center in Uzbekistan

The Center for Islamic Civilization – a global platform leading towards enlightenment