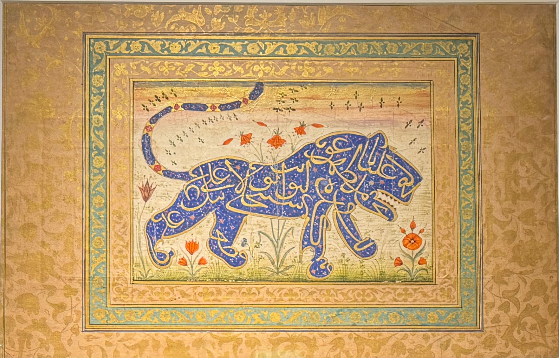

A tiger-shaped calligram brought from the United Kingdom is in Tashkent!

In a rare calligram dating to the late seventeenth century, letters come alive and transform into the image of a powerful tiger. Today, this unique work is on display at the Islamic Civilization Center in Uzbekistan, vividly demonstrating how text, image, and symbol merged into a single aesthetic system in the art of Islamic calligraphy.

Calligraphy is one of the most complex and subtle branches of the art of writing, in which letters are not merely carriers of meaning but appear as independent visual forms. Within the Eastern calligraphic tradition, this style erased the boundary between writing and image, elevating text to the level of an artistic form imbued with aesthetic and symbolic meaning.

In calligrams, the direction of each line, the curvature of letters, their density, and the balance of empty spaces are calculated in advance. For this reason, such works are not only read but, in the fullest sense, “seen.”

Calligram. In the style of Mir Ali Heravi. Herat, 17th century. Paper, gilded, 38 × 26.4 cm

The highest examples of this art in Eastern calligraphy were formed within the school associated with the name of Mir Ali Heravi. Active in the Herat milieu in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, this great calligrapher refined the nastaliq script to perfect standards and elevated writing to the level of an independent art. For this reason, many calligrams created in later centuries have been described as being “in the style of Mir Ali Heravi.” This designation signifies not specific authorship, but rather affiliation with a high artistic tradition.

A vivid example of this tradition, the late seventeenth-century calligram is currently on open display in the Second Renaissance period section of the Islamic Civilization Center in Uzbekistan. The work belongs to the Safavid period and is scientifically recorded as having been created in the Bukhara or Herat milieu. During this era, calligraphy was not limited to book decoration, but was regarded as an important expression of court culture and refined aesthetic thought.

The calligram presented in the exhibition depicts a tiger advancing forward, its entire body formed from letters and words written in Arabic script. The work is not a simple image, but a complex artistic solution based on the harmony of text and form. The tiger’s body, legs, and tail are rendered through curved and elongated inscriptions, with the rhythmic arrangement of letters conveying the animal’s movement and inner power. The denser treatment of the script in the head area further enhances the sense of focus and majesty.

In such works of art calligrams it is customary to employ the names of God, prayers, or phrases conveying power and protection. The textual content harmonizes with the image of the tiger, creating symbolic meaning. In Islamic art, and particularly in the art of the Mughal period, the tiger was regarded as a symbol of strength, courage, authority, and military power. The floral and vegetal motifs surrounding the image express ideas of blessing, life, and order.

The work is executed on gilded paper, using colored pigments and gold leaf, indicating that the calligram was created on the basis of a high-status commission. The composition is framed by reddish and green borders, while the inner field is filled with vegetal ornaments and fine gilded arabesques. These decorations reinforce the rhythm of the script and unite the entire work into a single visual system.

According to the Scientific Secretary of the Center, Rustam Jabborov, the reverse side of the work contains a twelve-line diagonal calligraphic text written in black ink in nastaliq script and placed among cloud motifs.

“Such a solution is rare in seventeenth-century manuscript art and requires exceptional skill. The black seal impression at the upper part and the double-bordered frame indicate that the work was used in an official context and was likely created on a courtly or high-ranking commission,” says Rustam Jabborov.

The uniqueness of the calligram is not limited solely to its artistic quality. The work was identified, authenticated, and examined through the world’s most prestigious international auction houses, such as Sotheby’s and Christie’s in the United Kingdom, and only then brought into the Center’s exhibition. This confirms its high valuation on the international art market and its unquestionable historical significance.

Today, the presentation of this calligram to the general public is an important cultural event. The work also holds special value as a historical document that provides a direct source for studying the art of writing, aesthetic thought, and artistic standards of the late seventeenth century.

Laylo Abdukakhkharova

P.S. The article may be republished with a link to the Center’s official website.

Most read

Over 100 experts from more than 20 countries of the world are in Tashkent!

President of Serbia Aleksandar Vučić visited the Islamic Civilization Center in Uzbekistan

The Center for Islamic Civilization – a global platform leading towards enlightenment