For the first time in Uzbekistan, original historical miniatures of the Baburids will be exhibited

🔴 Secrets of miniatures preserved in British Museums to be revealed

The Baburid era became one of the brightest periods in the history of India. This dynasty ruled the country for 333 years, until the British invasion in 1858. The Baburids brought the culture of the Timurids to India and skillfully enriched it by blending it with local values, customs, and traditions.

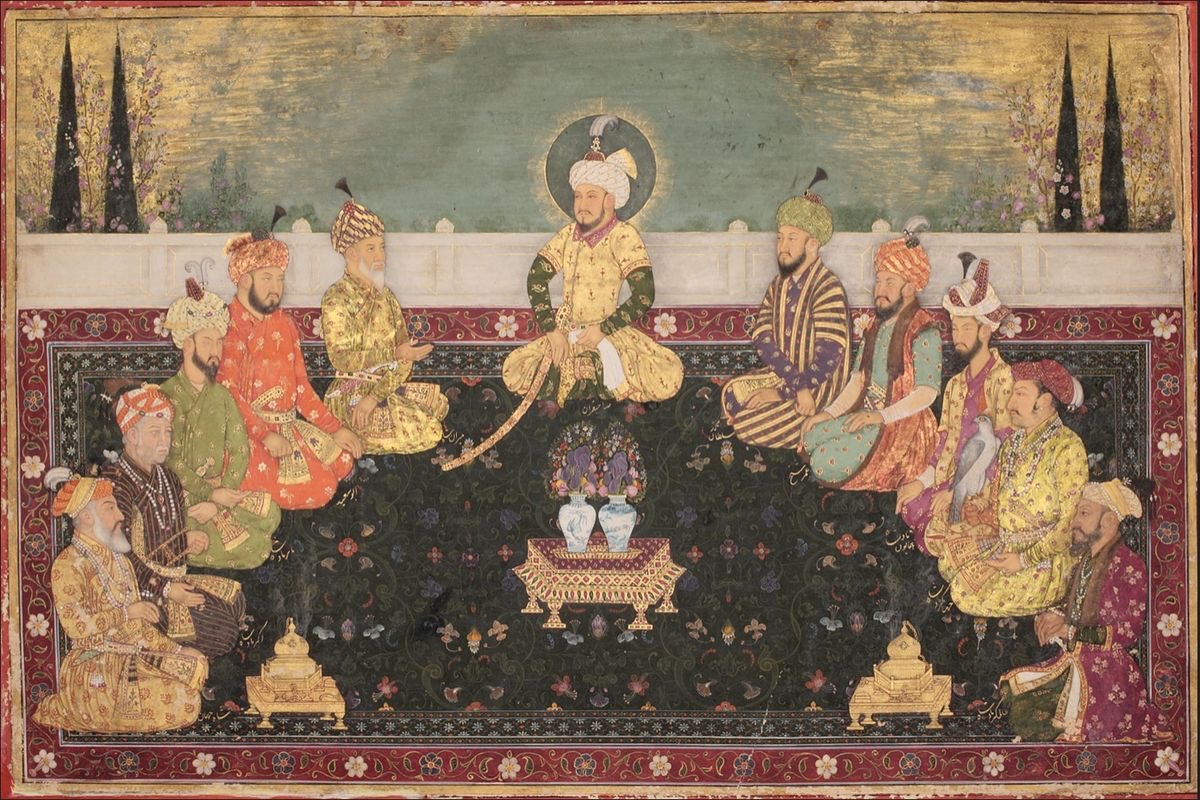

In the visual art of the Baburid period, one can see a distinctive harmony between local cultural elements and the artistic traditions of the Timurids. Representatives of the dynasty Babur, Humayun, Akbar, Jahangir, Shah Jahan, and Aurangzeb made significant contributions to the development of science, art, and culture in the country.

Overall, in the 15th–16th centuries, a new school of miniature painting emerged in India, combining the traditions of local Indian and Transoxanian visual art. The portrait miniature genre took an honorable place in the art of the time it became not only an important form of artistic expression but also an essential element of state policy. There were several reasons for this.

Firstly, almost all the Baburid rulers, who were representatives of the Timurid dynasty in India, regarded themselves as the legitimate heirs of Timurid culture. In accordance with Timurid traditions, the Baburid rulers showed great affection for art and paid close attention to book ateliers and painters. They wanted their portraits to be preserved for future generations a desire that greatly influenced the flourishing of Baburid miniature and portrait art in the 16th–17th centuries.

The Baburid rulers held the great painter Kamoliddin Behzad in high esteem and carefully preserved his works. Court miniaturists copied his paintings and learned from his mastery in creating lifelike portraits.

The Baburid school of portrait art eventually surpassed those of Iran and Transoxiana. This was largely because Baburid rulers required their portrait artists to capture the sitter’s physical likeness with the highest possible accuracy. To fulfill this demand, the most talented court painters were granted the right to accompany rulers on military campaigns and various ceremonies, where they could observe them directly and later use those observations in their portraits. Some artists were even included in diplomatic delegations to foreign countries to paint portraits of influential rulers abroad. As a result, among the portraits created in the Baburid court, one can also find depictions of rulers from Iran, Central Asia, the Ottoman Empire, and even Europe.

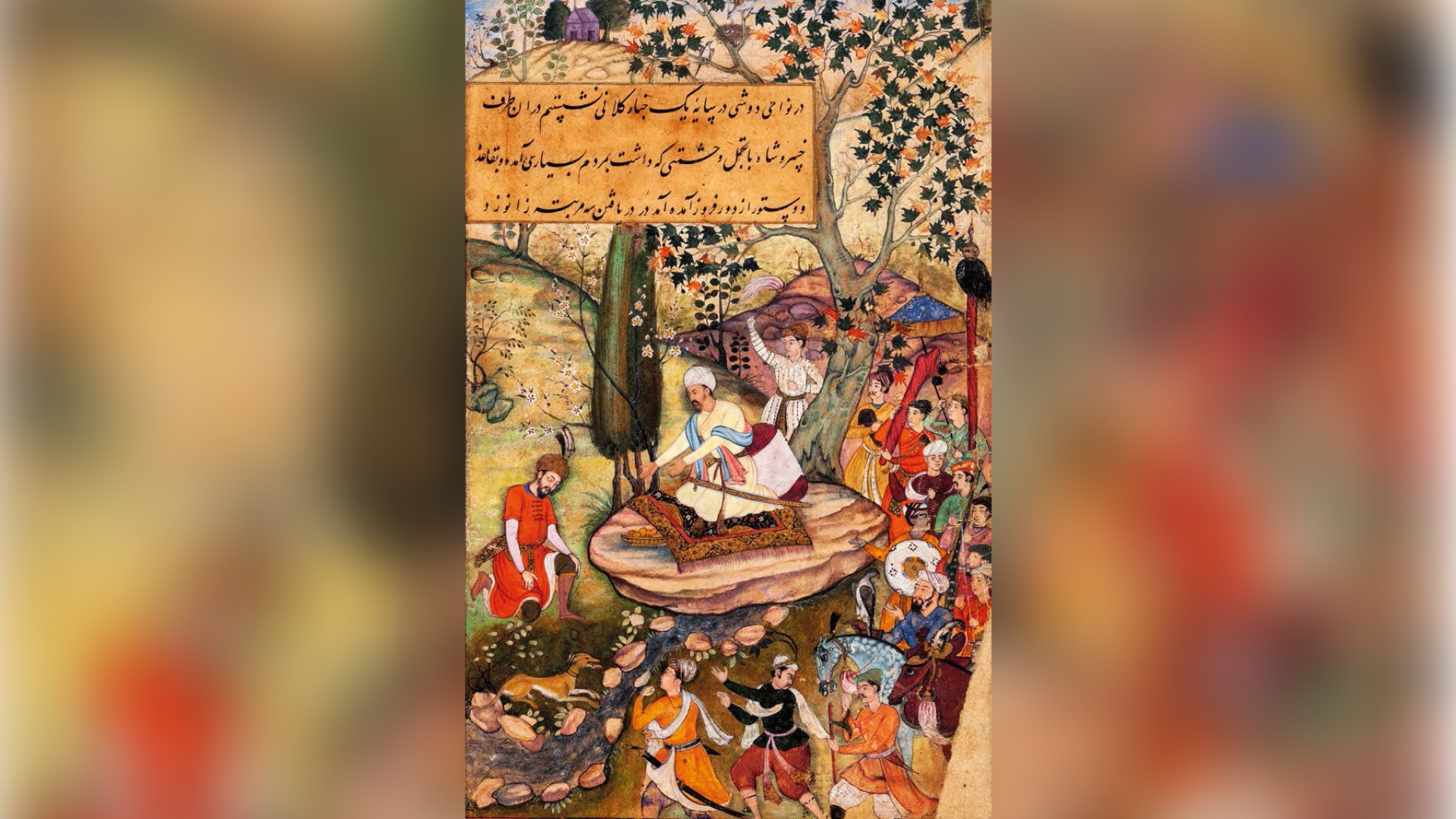

All generations of the dynasty showed great respect and reverence for their founder, Babur, and included his portraits in the illuminated manuscripts of their time. It remains unknown whether any portraits of Babur were created during his lifetime. The famous miniature depicting Babur reading a book in a garden while wearing a red turban later became the basis for numerous works of visual art. Today, this miniature is preserved in the British Library in London.

This portrait was created in the first quarter of the 17th century, during the reign of Babur’s grandson Jahangir. It depicts Babur sitting by a stream in a garden, barefoot, with his legs crossed, reading a book. Several deer are illustrated on the king’s robe. Babur wears a turban with yellow stripes, adorned with an aigrette a symbol of sovereignty and nobility.

Another portrait of Babur is believed to have been painted during the reign of his grandson Shah Jahan, around 1630. This miniature is housed in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. It is placed on a page of a muraqqa (album of paintings and calligraphy), with an inscription on the border identifying the depicted figure as Babur. On the reverse side of the page is the signature of Shah Jahan’s son, Dara Shikoh.

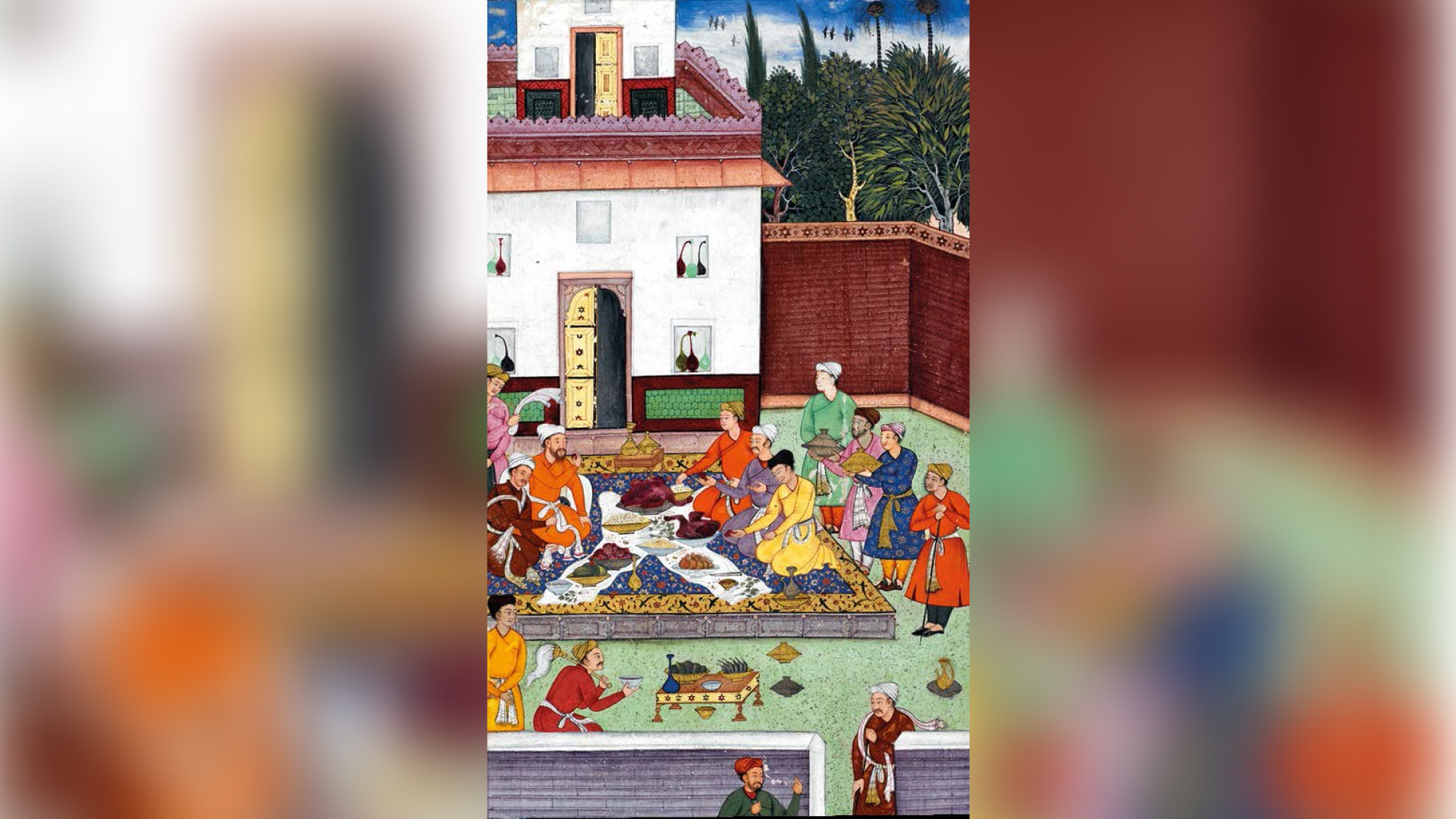

In various copies of the Baburnama manuscript created over time, Babur is depicted in different settings. He is portrayed in everyday life, at royal banquets, during hunts and military campaigns, and amidst the breathtaking nature of India as a great commander and ruler who was not a stranger to the simple joys of human life.

The earliest surviving portraits from the Baburid painting atelier were created by artists from Khorasan, Iran, and Transoxiana. Around 1540–1550, they entered the service of King Humayun in Kabul, and some later followed him to Delhi.

The painters’ inclination to depict specific historical figures took shape during the reign of Babur’s grandson Akbar (1556–1605). In the fragmented landscape of India at the time, Akbar’s destiny was to play an exceptional role. Through significant reforms, he managed to unite numerous small principalities and autonomous provinces under his command, establishing a powerful centralized state that remained strong for nearly a century after his death.

From his Timurid ancestors, Akbar inherited not only the qualities of a brave commander and an outstanding statesman but also the virtues of an enlightened monarch. He possessed a deep understanding of philosophy and literature, wrote poetry himself, had a keen interest in music, and received lessons in painting during his youth. During Akbar’s reign, numerous royal workshops were established, where craftsmen, blacksmiths, weavers, painters, and jewelers from different parts of India, Iran, and Central Asia were invited to work. Special attention was given to the visual arts, as Akbar’s political views were also reflected in artistic creations.

When Jahangir came to power (1605–1627), Baburid portrait art developed even further. Unlike before, particular attention began to be paid to the individual styles of artists. They started signing their names in the margins of miniatures and indicating the names of the figures depicted.

Under Emperor Jahangir’s rule, portraiture became the leading genre of Baburid visual art. In his royal gallery worked many great portrait painters, including Hashim, Govardhan, Abul Hasan, Daulat, Bichitr, Bishan Das, and others. Jahangir had such a profound knowledge of the visual arts that he could easily identify the works of any painter in the Baburid court.

At the exhibitions of the Center for Islamic Civilization in Uzbekistan established on the initiative of the President of the Republic of Uzbekistan visitors can explore the cultural heritage of the Baburid era, particularly the finest examples of miniature art. These miniatures, created between the 17th and 19th centuries, depict numerous representatives of the dynasty, court officials, and prominent figures of culture and art. For the first time in Uzbekistan’s history, original Baburid miniatures are being exhibited in our country.

Rustam Jabborov

P.S. The article may be used with reference to the official website of the Center.

Most read

Over 100 experts from more than 20 countries of the world are in Tashkent!

President of Serbia Aleksandar Vučić visited the Islamic Civilization Center in Uzbekistan

The Center for Islamic Civilization – a global platform leading towards enlightenment