“Forty centuries of words, thirty-six years of state language: the historical journey of the Uzbek language”

According to our scholars, the earliest roots of the Uzbek language date back to millennia before the Common Era. Some Turkologists, while analyzing one of the world’s most ancient written sources the Epic of Gilgamesh, composed in the ancient Sumerian language identified nearly 300 words and expressions that are still actively used in Turkic languages today, including modern Uzbek. Remarkably, words such as oz (few), yoz (write/summer), er (man), qiz (girl), buz (destroy), qush (bird), and qosh (eyebrow) have retained their form and meaning for 30 to 40 centuries.

In the 1890s, Danish scholar Wilhelm Thomsen discovered massive inscribed stone monuments in present-day Mongolia. At first, these inscriptions sparked extensive debate among researchers. Later, they became known worldwide as the Orkhon Inscriptions the oldest known monuments of Turkic peoples. It was established that they were written between 680 and 745 CE, during the “golden” age of the Turkic Khaganate, in the Old Turkic (Kokturk) language using the runic script. Although the three main steles Kül Tegin, Bilge Khagan, and Tonyukuk represent the most exquisite examples of all Turkic languages, their style, rhythm, and clarity bear striking similarities to the Uzbek language. Expressions such as “qaghanliq budun (el) erdim, qaghanim qani?” (“I was a nation with a khagan; where is my khagan now?”) from the Bilge Khagan Inscription illustrate how harmoniously our language resonates with the ancient Kokturk tongue.

According to historical sources…

Several written records confirm that the Old Uzbek language was once used on a much wider scale than it is today. This language served as a medium of communication across an immense territory stretching from central China in the East to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the West, and from the Golden Horde in the North to Egypt in the South.

During the Qing Empire (1644–1911) in China, inscriptions were discovered on the gates of the Summer Mountain Palace located in the Hebei province. These inscriptions were written in Chinese, Mongolian, Manchu, Chagatai (Old Uzbek), and Tibetan. Above the main gate, an inscription in pure Turkic language written in nasta‘liq script reads: “Rawshan: the middle gate.” Scholars note that the Old Uzbek (Chagatai) language was among the five most important languages used during the Qing period.

An Ancient Dīvān Found in Egypt

In 2012, an ancient dīvān (collection of poems) written in the Oghuz dialect by Alisher Navoi was discovered in the National Library of Egypt. This was not the first Turkic manuscript found in the land of the Pyramids. Historical accounts state that the great Uzbek poet Sayfi Saroyi spent the final years of his life in Egypt, where he composed several poems and epics in the Uzbek language.

“Spears have grown over my homeland’s soil, I have been torn from my home,

Vanished from my motherland — turned into a stranger in a foreign land.”

It is also known that one of the brightest works of Turkic literature, Qutadghu Bilig by Yusuf Khas Hajib, was found in the basement of the Cairo Library. Moreover, in present-day Cairo there still exists a historical neighborhood called Uzbekiya, along with a street, mosque, theatre, and park bearing the same name.

The Special Decree of Amir Temur

During the reign of Amir Temur (1370–1405), the Great Conqueror ordered that official decrees, royal edicts, and stone inscriptions intended for future generations be written in the Old Uzbek language. The earliest manuscript of the Tuzukot-i Temur (The Codes of Temur) was also composed in the mother tongue.

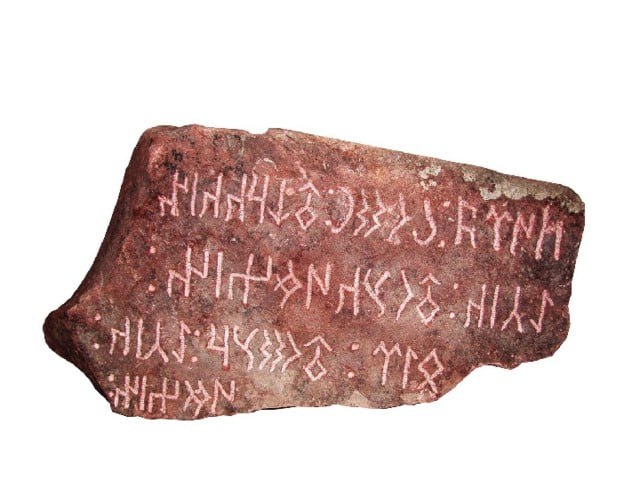

In 1391, during his campaign against Tokhtamysh Khan of the Golden Horde, Amir Temur left a stone inscription at the foot of Mount Ulugh (in modern-day Karaganda region of Kazakhstan). This inscription vividly demonstrates the clarity and beauty of the Uzbek language in the Temurid era:

“In the year 793 of the Hijra, in the year of the Sheep, during the month of Summer, Sultan of Turan, Temurbek, marched with three hundred thousand troops for the cause of Islam against Tokhtamysh Khan, the ruler of Bulghar. Having reached this place, he raised this mound as a sign. May God grant victory, InshaaAllah. May God bless the people of the land and remember us in their prayers.”

Those who preferred another language over their own

No matter how much we speak about the immense contribution of the “Sultan of Poetry,” Mir Alisher Navoi, to the development of the Uzbek language, it will never be enough.

“In the realm of Turkic verse, I endured pain,

Until I made that land my own domain,”

with these lines, the great poet justly acknowledged his tremendous role in elevating the prestige and influence of our language in his era. Through his rich literary legacy, Navoi practically demonstrated the superiority and expressive power of the Turkic tongue over others. In his work Muhakamat al-Lughatayn (The Comparison of Two Languages), Navoi emphasized the advantages of the Turkic language and, with deep regret, spoke about poets and scholars who considered foreign languages superior:

“Among this people, there have arisen men of talent and ability; yet though they possessed their own tongue, they did not manifest or employ it. And if they had the capacity to express themselves in both tongues, they should have spoken more in their own and less in another…”

Sadly, even in those times, there were individuals who failed to fully grasp the greatness, richness, beauty, and uniqueness of our language those who did not truly value its worth.

A Language that Unites 50 Million People

Today, we can proudly say that the Uzbek language is rising to new heights. Among nearly seven thousand languages spoken worldwide, Uzbek holds a distinct place, status, and recognition a fact that fills all of us with pride.

The Turkic language family, to which our mother tongue belongs, includes more than 30 languages spoken by over 250 million people across the globe. The total number of Uzbek speakers worldwide now reaches about 50 million.

It is also a source of pride that Uzbek is among nearly one hundred languages with official state status. Considering that there are around 7,000 languages and dialects in the world, this is an impressive achievement especially given that some languages spoken by hundreds of millions still lack state status.

On October 21, 2019, the President of Uzbekistan signed a decree “On Measures to Radically Increase the Prestige and Role of the Uzbek Language as the State Language.” Based on this, October 21 the date when the Law on the State Language was adopted was officially designated as the Day of the Uzbek Language. This year marks the 36th anniversary of the Uzbek language receiving state status.

Rasul Hamzatov’s Dream

Once, the great son of Dagestan, Rasul Hamzatov, wrote about his native tongue:

“Though my mother tongue is not heard from the world’s grand tribune,

It remains sacred and great to me.”

What happiness it is that our mother tongue now does resound from the tribunes of the world. Indeed, today every Uzbek can proudly say they have achieved the honor that Rasul Hamzatov once dreamed of.

A Civic Duty

The state language, like all national symbols, is sacred. According to a recently adopted regulation, any individual seeking citizenship of the Republic of Uzbekistan must possess an adequate command of the state language. Such a requirement is common in many countries. In the legal frameworks of our neighboring and fraternal nations as well, every citizen is obliged to know the state language. Therefore, anyone who considers themselves a part of this land must respect the state language and comply with the laws related to it.

What’s happening at the Center for Islamic Civilization in Uzbekistan?

The Center for Islamic Civilization in Uzbekistan is actively carrying out large-scale efforts to preserve and promote the rich spiritual heritage, ancient culture, and millennia-old history of our people. At present, the Center houses priceless literary monuments written in the Uzbek language rare manuscripts of great thinkers and poets such as Lutfiy, Alisher Navoi, Zahiriddin Muhammad Babur, Boborahim Mashrab, Turdi Farog‘iy, Muhammad Rizo Ogahiy, and others.

Moreover, within the framework of its scientific and innovative projects, the Center is conducting research dedicated to the history, evolution, and development of the Uzbek language.

Durdona Rasulova

P.S: The article may be republished with a link to the official website of the Center.

Most read

Over 100 experts from more than 20 countries of the world are in Tashkent!

President of Serbia Aleksandar Vučić visited the Islamic Civilization Center in Uzbekistan

The Center for Islamic Civilization – a global platform leading towards enlightenment