History carved in stone: The astonishing drawings of the Nurata mountains

🔴Heritage recognized by UNESCO: About the oldest gallery in Uzbekistan

We often study history through books, manuscripts, or archaeological finds. But humanity’s oldest memories are preserved not only on paper but also engraved on rocks. A vivid example of this is rock art — petroglyphs.

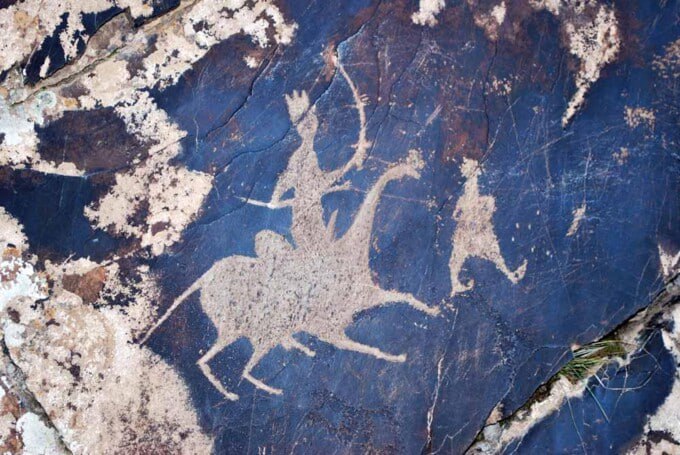

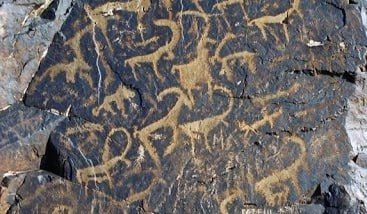

Uzbekistan is home to many such monuments. Particularly, the Sarmishsoy and Qorong‘iungursoy gorges in the Nurata mountain range have amazed scholars worldwide. Through the images here, we can glimpse the daily lives of our ancestors, their hunting scenes, religious beliefs, and even their spiritual world.

Early discoveries

Interest in rock art began in the 19th century. In 1834, Russian army officer P.I. Demezon discovered the first petroglyphs at Bukantog in the Kyzylkum desert. Later, Orientalist scholars such as V.V. Bartold, N.I. Veselovsky, and G.I. Pantusov conducted scientific research in this field.

Starting in the 1950s, Uzbek archaeologist Kh. Mukhammadov, relying on information from local residents, began studying Sarmishsoy. As a result, the Nurata mountains became the largest petroglyph center in Central Asia.

An open-air museum

To date, more than 10,000 images have been found at Sarmishsoy. They depict hunting scenes, humans, animals, totems, weapons, chariots, and religious symbols. In one image, a hunter shoots an arrow at a camel with a bow; in another, wolves attack mountain goats.

Why did they carve on rocks?

Ethnographers offer various explanations:

Some believe they were created due to religious or totemic views.

Others think they served as a form of writing, marking the areas where a tribe hunted.

Scientific research

In the 1960s, a group led by academician Ya. G‘ulomov classified the Sarmishsoy petroglyphs into three periods:

➖ Bronze Age — animals and hunting scenes;

➖ Early Iron Age — weapons, totems, pastoral scenes;

➖ Later periods — religious symbols, human figures, and everyday life scenes.

International recognition

Since the 1990s, Uzbekistan–Poland and Uzbekistan–Norway expeditions have carried out research here. In 2010, the Sarmishsoy petroglyphs were included in UNESCO’s Tentative List of World Heritage Sites.

Preservation challenges

However, this unique heritage is under threat: natural factors (wind, rain, snow) and human impact (graffiti, heavy machinery) are accelerating the loss of these drawings. For this reason, in 2004 Sarmishsoy was given the status of an “open-air museum-reserve.”

A replica of these petroglyphs has been given a special place in the Pre-Islamic Civilizations section of the Center of Islamic Civilization in Uzbekistan.

Durdona Rasulova

P/S: This article may be republished with a link to the official website of the Center.

Most read

Over 100 experts from more than 20 countries of the world are in Tashkent!

President of Serbia Aleksandar Vučić visited the Islamic Civilization Center in Uzbekistan

The Center for Islamic Civilization – a global platform leading towards enlightenment