I have pain...

Of course, the title given to the article may seem to give the overall content a somewhat somber tone. However, there is no reproach in it at all. We are far from any intention of condemning the past or harboring resentment toward those who came before us. Moreover, in order to appreciate the value of our bright present and our current achievements, there is no need to deliberately search for examples in the dark corners of history. At this point, a natural question arises: if everything is as it should be, then why the pain?

Qudratilla Rafiqov,

Political Scientist

“Legends do not live on their own. They wait for us to breathe life and blood into them. If even a single person in the world answers their call, the legends stand ready to water us with an endless spring of life. Our task is not to forget them. We must act so that no legend falls into the sleep of death”, Albert Camus once said.

Sadly, although not entirely the same, this idea is strikingly close to our situation. Indeed, for many years we forgot our legendary history, our culture, who our ancestors were, and where our place was in this world. We became accustomed to being seen as living at the edge of the world, as a third-rate country and nation. Most painful of all, our cultural and historical place on the modern world stage “vanished” like water seeping into sand. The words “Uzbek” and “Uzbekistan” lost their true meaning and were reduced to mere geographical references on a map. The suffix “-stan” in our country’s name became confused with other “-stans” and was often mentioned casually or even mockingly...

If we take a serious look at our reality, the words of a well-known foreign political scientist fit perfectly: “...on the whole, today many people abroad no longer regard the land of Ibn Sina and al-Biruni with respect, but rather as a troubled region that must be crossed to reach some other destination.” Yes, he was right about that. We should not be offended by his statement, because the reality was indeed no better.

And yet, as that political scientist pointed out, our homeland, in terms of intellectual and cultural heritage and political-military traditions, does not deserve to be “lost” among the other “-stans” as we said above.

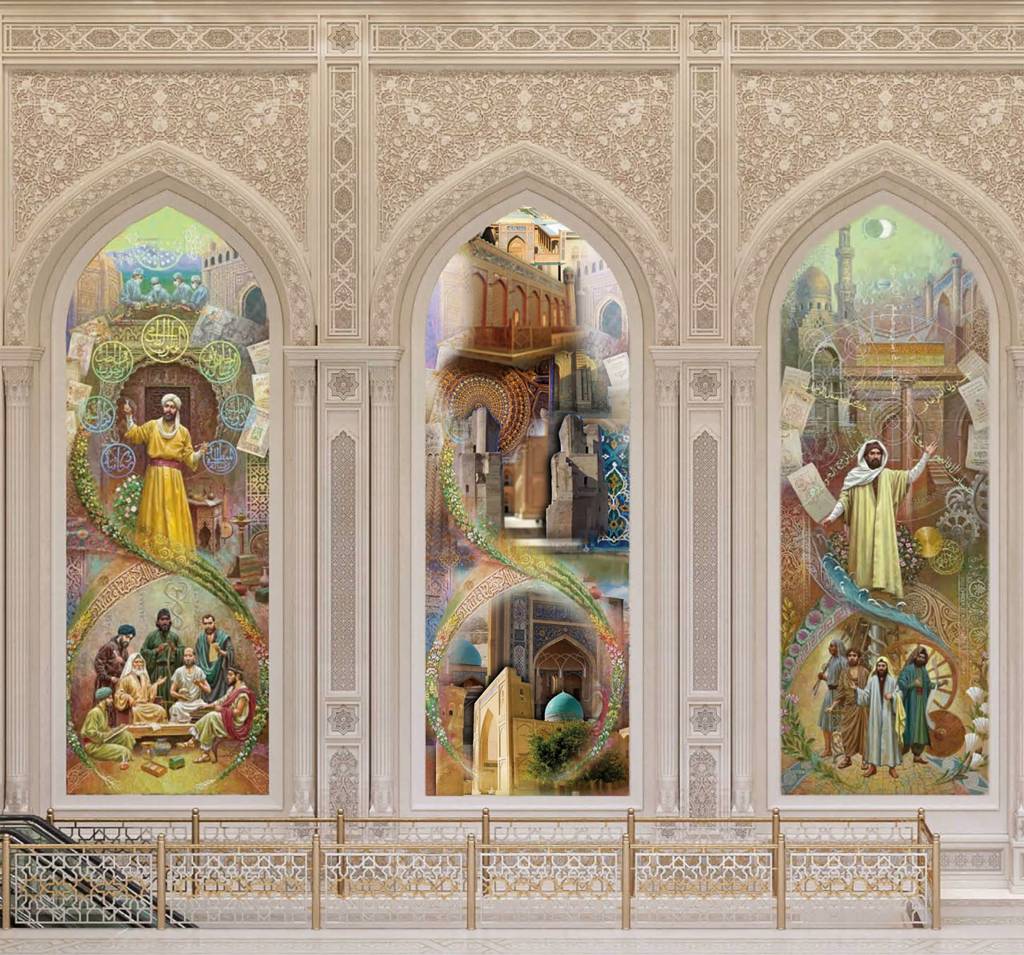

This land was the cradle of two great renaissances that left an indelible mark on human history — the Islamic Renaissance and the Timurid Renaissance. It was the center of mighty empires and kingdoms that ruled half the known world.

But where is that history now, where are those memories that once granted us honor, glory, and greatness?!

Anyone who has even a slight knowledge of our history and identity will inevitably be plunged into deep thought by this question, and such reflections quietly stir the pain within their heart...

I believe that astute analysts and enlightened individuals can clearly see and feel the path Uzbekistan has now embarked upon and what is taking place here. However, there is one subtle point that I doubt everyone notices. I remain firm in the opinion I have expressed in several of my previous articles that this land and its people, who for so many years were forced to endure many misfortunes, are now committed not only to strengthening the sovereignty of the state but also to restoring the glorious memory of their forgotten and uprooted past, reviving their culture and ancestral heritage, and through this noble effort, rediscovering their identity and embarking on a path of spiritual renewal.

A fragment of the Kiswa presented to the Center of Islamic Civilization.

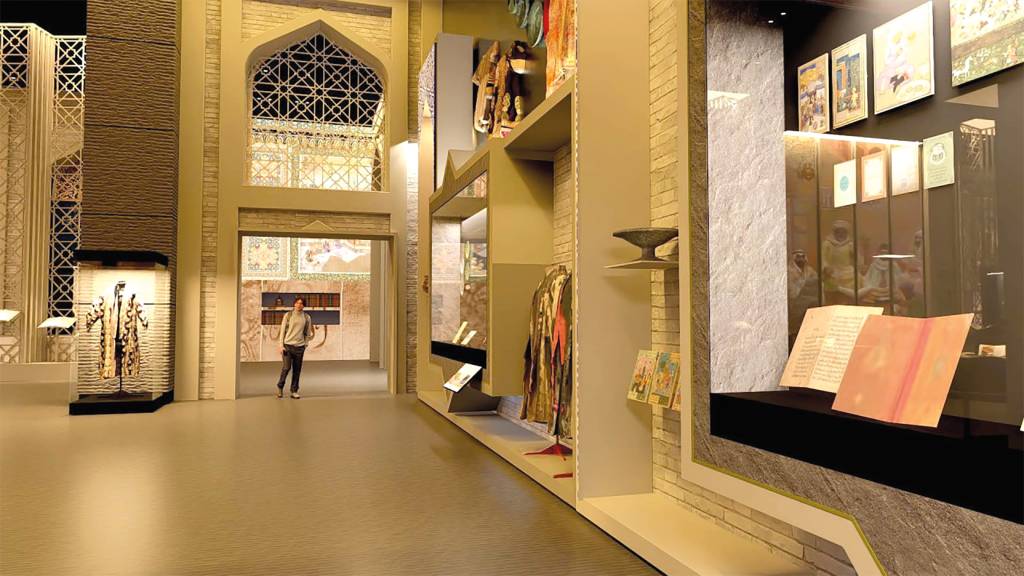

Imam Bukhari innovative museum hall

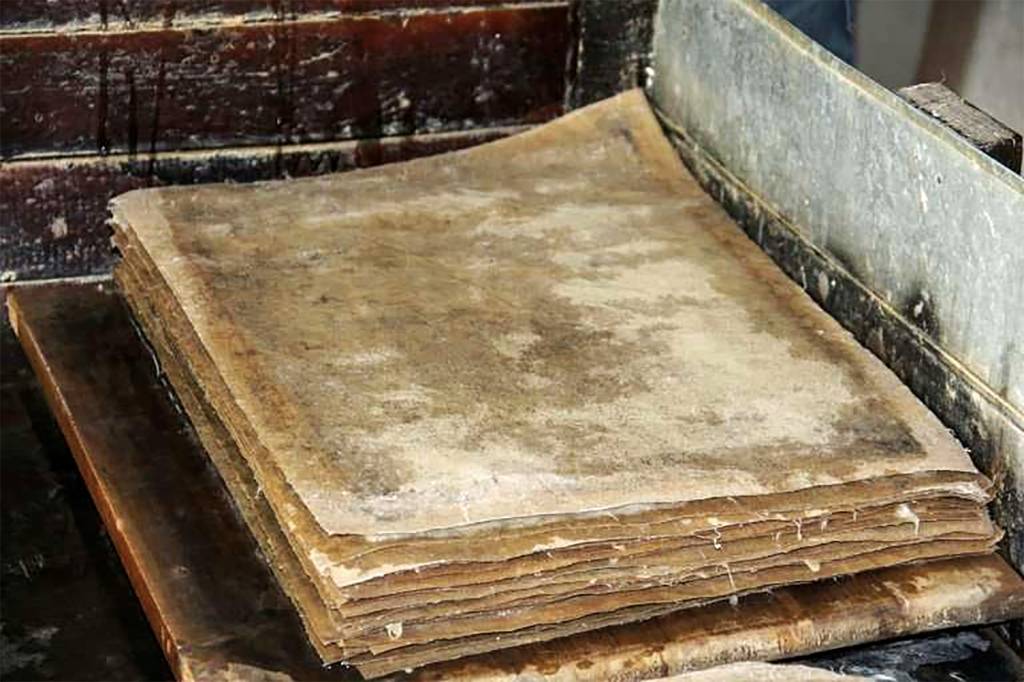

An ancient manuscript of the Holy Qur’an

The Time Wall project at the Center of Islamic Civilization

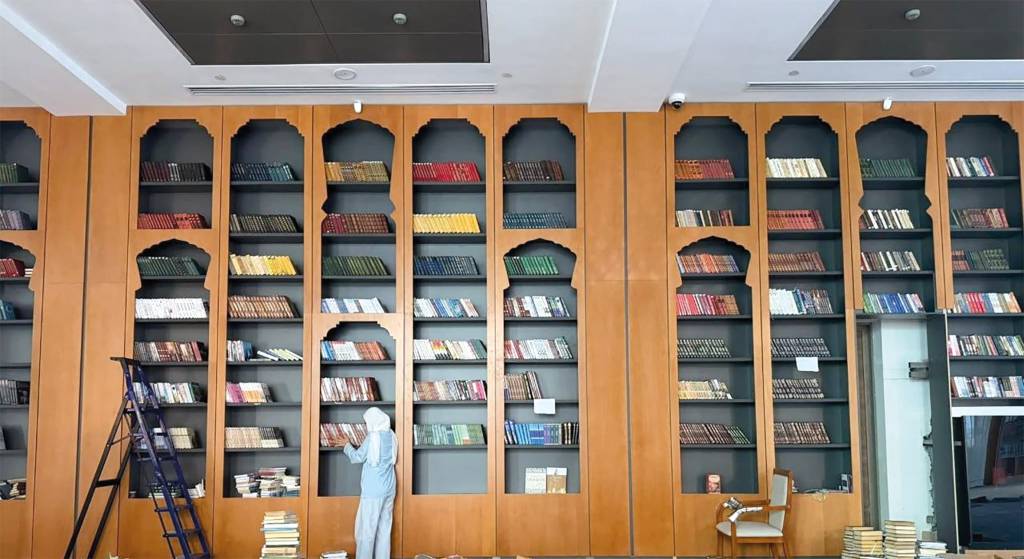

Second Renaissance Hall

The time has come for me to speak openly about one issue, since it is directly connected to today’s article. I clearly remember that when the topic of a Third Renaissance was first raised in our country, and this idea was voiced from high tribunes, some people reacted to it with ridicule. I would be lying if I said that such attitudes no longer exist today there are still people who hold these views. The problem is that such individuals see only the surface layer of the policy being pursued.

The “otherness” of the Shavkat Mirziyoyev phenomenon lies in the fact that he never ostentatiously expressed the burning love he carries in his heart for his nation and homeland, nor did he pay attention to those who dismissed or mocked him. However, anyone who carefully observes his activities can discern the true picture and fiery idea reflected in the President’s character.

“...Why did we create the Center of Islamic Civilization? To etch the honor and glory of our nation into history. We built this so that when a person enters this place, they leave with a sense of reverence for this nation...”

This quotation is taken from the President’s live speech during his meeting with community leaders on the eve of this year’s Independence Day. The following excerpt, however, is from his 2023 speech:

“When we look back at the past, we are forced to acknowledge a bitter truth: when the word ‘Uzbek’ was mentioned, people imagined a laborer working in the cotton fields from dawn to dusk. Unfortunately, we had sunk to such a state.

The dominance of cotton became a disaster written on the Uzbek nation’s forehead. The cotton policy dried up the Aral Sea, led to an ecological crisis, disrupted our economy and education system. As a result, several generations grew up half-educated. We are still fighting against the consequences of this”.

At first glance, a reader comparing these two quotations may wonder what one has to do with the other, and that is natural, since they belong to different periods and contexts. But the reason we place them side by side in this article is deliberate this very approach helps to interpret the President’s inner world, to guess at his hopes and aspirations, and to identify the true idea that drives him.

Indeed, if you pay close attention to the subtext of these quotations, you will see that their hidden rhetoric can make them converge into a single meaning. That is, the President’s thoughts and appeals about renaissance and spiritual revival are not mere political populism but a concept built on a fundamental basis and a clear plan. Notice this: the idea of building the “Center of Islamic Civilization,” which we have taken as the main topic of this article, was proposed by the President in 2017, right when he had just assumed office, and this grand initiative was set in motion.

It was in those very years that the notions of a Third Renaissance, a new attitude toward our historical and cultural heritage including the Islamic and later Timurid Renaissances and the memory of our great ancestors became the core of President Shavkat Mirziyoyev’s ideological policy. In short, it sometimes seems as though there is a single longing that has lived in his heart and troubled him constantly: to restore the dignity of the nation and the homeland, to exalt the honor and glory that were trampled upon and, at times, humiliated...

I have had the privilege of hearing that man speak many times about the history of our people and our homeland: “Why is it that when someone mentions ‘Uzbek’ or ‘Uzbekistan,’ they always think of cotton, pilaf, a skullcap and a chapan, cotton-flower teapots and bowls, teahouses and hospitality — do we truly have nothing else of value to show the world, nothing that represents us? Why don’t we proudly present to the world the great heritage of our ancestors, who conquered the world and enthralled it with their knowledge and enlightenment? Why do we shy away from this great historical memory, hide it, pretend it doesn’t exist, hesitate to speak the names of the great ones, and fear to make their heritage known to the people? Was it not these very giants who taught humanity everything from mathematics to medicine, from astronomy to philosophy and music, and who laid the foundations of many branches of modern science? Were they not our own forefathers who built empires from the Altai to the Mediterranean, from Egypt to India, and held the world to account?.. And why are we in such a state today? Why do our children carry hunched shoulders, lowered heads, and eyes fixed to the ground?..”

It has been nearly thirty years since I first heard these words from Shavkat Miromonovich himself. And I know for certain that throughout all these years, this inner pain the pain of the nation has spiritually shaped and raised him as a true patriot, a devoted son of his people and homeland.

Indeed, his inner reproach was not baseless — it was entirely just. To put it with a touch of literary passion, it sometimes felt as if history itself was being unjust to us. But the undeniable truth is that the scientific ideas and discoveries created by our great ancestors opened entirely new pages in the development of world science and civilization — not only in the exact sciences but also in history, geography, philosophy, culture, art, and architecture.

For example, the numeral system founded by our great forefather Abu Musa Muhammad al-Khwarizmi, the Canon of Medicine written by Abu Ali Ibn Sina, Abu Rayhan al-Biruni’s remarkably precise measurement of the Earth’s radius using a simple astrolabe, and the fact that Christopher Columbus reached the shores of America in 1492 guided by calculations based on Ahmad al-Farghani’s determination of the Earth’s degree all of these testify to the boundless intellect and scientific potential of our ancestors.

Furthermore, the fact that Samarkand paper was once considered the highest quality in the world, and that the decorations of Europe’s most prestigious palaces and cathedrals were made from silk produced in the Fergana Valley, also serves as clear evidence of the priceless significance of our material and spiritual heritage.

An even more vivid and fascinating fact is cited by the well-known American political scientist Frederick Starr in one of his articles. Speaking about the first renaissance, he notes:

“...The last great ‘explosion of cultural energy’ in Central Asia occurred under the rule of the Seljuk Turks and lasted for over a century, beginning around the year 1037. From their eastern capitals — present-day Merv in Turkmenistan and Nishapur on the Afghanistan-Iran border — they supported innovators in many fields. One of their achievements was the development of the double dome, covering vast spaces. The early fruits of this achievement can still be seen today in the neglected ruins of Merv. Beginning its ‘journey around the world’ with Filippo Brunelleschi’s dome in the Florence Cathedral and continuing through the dome of St. Nicholas’ Cathedral in St. Petersburg, this invention ultimately found its reflection in the dome of the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C.”

Indeed, this well-deserved recognition shows that our ancestors were unparalleled even in the art of architecture. But today, apart from a handful of specialists, who knows this and acknowledges it? Who is out there promoting the fact that our people and our homeland possessed such immense potential?.. Even back then, I saw this very sorrow, these frozen questions, reflected in Shavkat Miromonovich’s words and in his eyes...

In the middle of the last century, a European philosopher, writing about the calamities and horrors of the wars that engulfed his era, his continent, and the world, said: “If, in such a terrifying age, painters could calmly paint pictures of hens ‘dozing’ in their coops, then mankind’s faith in beauty, creativity, peace, and goodness has not yet been extinguished”.

Nearly a century later, I feel I can add this: at a time when the world stands on the brink of nuclear catastrophe (and let us not forget, our region borders four nuclear powers), and worse still when one of the so-called guardians of the world order is talking about renaming its Ministry of Defense into a “Ministry of War,” who could deny the legitimacy of asking the question: what kind of heart must a person have to dare speak of human civilizations, ancestral heritage, art, eternity, and universal values, and to have the courage to take on great work in this direction? Or if I point out that Camus’s words that legends must not be allowed to fall into the sleep of death, that at least one person in this world must dare to answer their call and give them life and blood are not just a poetic metaphor but a historical necessity, what force could stand in my way?!

Naturally, the subject we are analyzing is worthy of such figurative language and philosophical reflection. For at the heart of this very idea lies not only the interests of the nation and the homeland but also a desire to steer humanity’s thought into a universal channel, to sound the bell of awakening over a world that is aging and becoming increasingly tiresome, to signal that goodness and beauty still exist. We will leave deeper reflections on this for a bit later.

For now, let us discuss another important issue. I have always said, with a certain inner regret, that when the topic of “Islamic Civilization” which has earned its firm place in the history of world culture is discussed on a global scale, our country and our people are often left “out of the equation.” In reality, however, this heritage, which holds universal value, belongs to us perhaps more than to anyone else.

Although Baghdad was the center of the Caliphate and some attempt to link this great Renaissance solely with the Middle East, and to attribute its great scholars to the Persian or Arab cultural worlds, the historical center and the main intellectual “base” still belong to us. This is a historical axiom.

Frederick Starr expresses our observations very convincingly and truthfully in one of his works: “...Although Caliph al-Ma’mun was appointed in 818 CE, he refused to leave Central Asia and governed the Muslim world from the unique city of Merv, located in present-day Turkmenistan. When he eventually moved to Baghdad, he took with him not only his Turkish troops but also the values of Central Asia — shaped by a mixture of Persian and Turkic cultural influences. This migration from Central Asia to the Middle East occurred in the same way that the ancient ‘migration of minds’ once moved knowledge from the Greek centers of learning to Rome”.

Oxford University researcher and historian Paul Wordsworth, speaking about the past of our region, discusses its once-crucial role in the global order. “Many people imagine that the vast landmass of Eurasia is seamlessly interconnected,” he said in an interview with the BBC. “But this is not the case, because Central Asia is home to the world’s highest mountains, and its long, untamed rivers flow through challenging landscapes.

By the middle of the first millennium CE, Central Asian merchants had gained the skill to traverse this difficult terrain and engage in trade. The region was not just the heart of trade routes — science and creativity also flourished here.

Scholars traveled from city to city, exchanging knowledge. Cities like Bukhara and Samarkand along the Silk Road became centers of learning. In their time, they were like the Oxford and Cambridge of Central Asia.

Too often, when the Silk Road is mentioned, people look only toward China or the Roman Empire. This creates the impression that the lands between were merely passive recipients of outside influence. The true history of Central Asia helps to dismantle these stereotypes. Indeed, the people of this region, with their intellect and unique culture, were able to connect the whole of Eurasia into one.

But the problem, as Wordsworth specifically notes, is that this land remained overshadowed by external powers for many years. Worst of all, even today there are those who try to portray us as merely the “backyard” of one great power or another and push us to the margins.

We must admit that our attitude toward history has shifted from period to period. There were times when we became its obedient servant, and times when we consoled ourselves merely by boasting about it. At times, we fabricated and tailored it to suit our preferences. To be frank, many know how we were taught to view the past during the Soviet era. Yet, even after independence, our attitude toward the cultural heritage of the past did not change very much.

True, it would be unfair to say nothing changed at all some initiatives were announced, some steps were taken but as I said before, they were often selective, done as we wished. On this topic, I would highlight the ensemble that begins in Shahrisabz, continues through Samarkand, and finds its full poetic expression in the very heart of Tashkent the majestic bronze statues of the great Sahibqiron (Amir Temur). The respect shown to the figure and legacy of our great ancestor was one of the most significant acts of the early years of independence. The decision to name the vast and grand square after him, as well as to build the State Museum of the History of the Temurids nearby, made our official attitude toward historical heritage even clearer.

In this sense, the image and majesty of Temur and his dynasty came to be seen as a symbol of our independence and statehood (and it should be noted that this idea was first raised by the Jadids in our recent history — and they did not limit their vision to the figure of Temur alone, but also drew inspiration from figures like the Turkic leaders Attila and Bilge Khagan, Uzbeg Khan, and even the controversial memory of Chinggis Khan). For a newly independent former Soviet republic, this was understandable and even commendable.

Yet there were exceptions that “disturbed” this comfort. At that time, although unofficially, our perspective on history took on a form such that it seemed to begin and end with Temur and the Temurids. Admittedly, this may sound a bit harsh, but the reality was not far from it. Yes, the names of scholars and personalities who lived a thousand years earlier were mentioned from time to time, sometimes included in speeches to embellish political texts, but the broadly recognized three-thousand-year history of our people was never fully acknowledged.

Perhaps it is precisely this former attitude toward our heritage that allows some people today to claim that Beruni, Khwarazmi, Ibn Sina, Farabi, and other greats belonged to Arab or Persian civilizations. In any case, such a view is strange and entirely illogical.

Just think: even back then, we would speak about the millennia-long history of our cities and culture, celebrate the 1,000- and 2,000-year anniversaries of certain ancient settlements and world-renowned scholars, yet at the same time, we strangely encouraged the notion that our national history began in the 14th century with the era of Temur. Most astonishing of all, the dozens of centuries before that and even the six centuries that followed were almost never mentioned, as if condemned to “exist” only in the manuscripts of scholars and writers. To put it mildly, this was essentially the subordination of history to ideology and politics. In other words, we curated the past, trimmed and shaped it, and used only those pieces that suited our political “needs”.

For instance, we might build a memorial complex and shrine in Yunusabad to immortalize the memory of the victims of repression, recite the Qur’an for them once a year, and raise our hands in prayer all partly to quell the emotions of intellectuals and the general public, and partly to present ourselves to the international community as a nation emerging from the “quagmire” of postcolonialism but we would never erase their names from the blacklists. The lists of those executed by order of the Supreme Court of the former Soviet Union and defamed as “enemies of the people” would remain untouched...

Well, that is a separate and very profound topic. I bring it up only because it reveals how sincere or insincere official policy has sometimes been. That is why I mention it briefly.

Now, let us turn to the subject we have taken as the basis of this article. As mentioned earlier, construction of this complex began in 2017. The project, located in the territory of Tashkent’s famous Hazrati Imam complex, covers an area of 10 hectares. The length of the majestic structure reaches 161 meters, and its width 118 meters. It consists of three floors. The height of the central turquoise dome is 65 meters. The building itself occupies 1.8 hectares, with a usable area of 42,000 square meters. These statistics alone show that the Center of Islamic Civilization in Uzbekistan, by its grandeur, scale, and scope, is destined to become one of the largest complexes in the world dedicated to the study and promotion of Islamic history, culture, and civilization.

Allow me, as someone who has personally seen this magnificent edifice and felt boundless pride and admiration, to describe it in more detail.

The complex is designed in accordance with Eastern and national architectural traditions and can be entered from four sides through four main portals. Each portal and the exterior façades are adorned with Qur’anic verses and hadiths promoting sacred values such as knowledge, enlightenment, tolerance, and respect for parents.

The museum of the Center will feature sections dedicated to the Qur’an, pre-Islamic civilizations, the First Renaissance, the Second Renaissance, the era of Uzbek Khanates, Uzbekistan in the 20th century, and New Uzbekistan – the New Renaissance. In addition, its second floor will host representative offices of international organizations, as well as branches of Al-Furqan, the Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies, and over 100 scientific institutes, museums, and libraries from Turkey, Russia, and other Central Asian countries.

What is particularly noteworthy is that the Center has also introduced a system for planning scientific research based on both local and international experience. At this point, I must mention an important thought so it is not overlooked: today we speak a great deal about the two great renaissances that were born in our land, but we rarely reflect on how exactly they came to life. History shows that these renaissances emerged through the exchange of cultures and integration into the global scientific community of their time.

The fact that the Center is establishing cooperation between many of the world’s leading scientific and cultural institutions and our own scholars and intellectuals means, simply put, that Uzbekistan is positioning itself to attract some of the world’s foremost minds (recall that Caliph al-Ma’mun and Amir Temur both gathered and encouraged the greatest thinkers of their time). This points to a future of tremendous opportunity.

It is also worth noting that in the construction of this complex and in the equipping of its museum and other cultural facilities, leading specialists and scholars from dozens of countries around the world took part. This is why I can confidently say that the Center’s fame spread across the globe even before its opening. Indeed, institutions such as the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia, the Suleymaniye Library (Turkey), the Azret Sultan Complex (Kazakhstan), the University of Bologna (Italy), the Ratti Foundation, the Alberto Levi Collection, the National Museum of History of Azerbaijan, and prominent U.S. collectors like David Peili, Bruce Baganza, and David Reisborn, as well as the State Hermitage Museum of Russia, the State Museum of the History of Religion in St. Petersburg, and the Marjani Foundation have all expressed their intention to participate with exhibitions at its grand opening ceremony.

While working on the process of organizing the museum’s operations, I noticed one more very important detail, which gave me great satisfaction. To be frank, in the past we would frequently hear painful reports in foreign media or on social networks saying that an ancient manuscript or artifact of historical value had been stolen from a museum or institute in Uzbekistan and smuggled abroad. Today, however, the news is not about theft but about the spiritual treasures of our people taken abroad by such illicit means being brought back home.

Most recently, for this museum, more than 580 artifacts related to Uzbekistan’s cultural heritage were purchased from London’s Sotheby’s and Christie’s auction houses, as well as from major collectors and art dealers. (Just think about it: nearly six hundred priceless items are being returned to us something unprecedented in our history.) Among them are a fragment of the enormous Qur’an manuscript copied by calligrapher Umar Aqta on the orders of Amir Temur (the Baysunghur Qur’an), two daggers and a sword from the Mughal period, an ornate dagger hilt, five embroidered textiles created during the Uzbek Khanate period of the 18th–19th centuries, three miniatures from the Mughal and Safavid eras, two golden ornaments from the Golden Horde, a copy of Jalal al-Din Rumi’s Masnavi-yi Ma‘navi from the Mughal period, a page from Hafiz-i Abru’s Majma‘ al-Tawarikh copied during the Timurid era, as well as ceramic and silver vessels from the Sogdian, Karakhanid, and Seljuk periods.

These acquisitions symbolize not just a replenishment of our cultural wealth but a restoration of historical justice — a revival of what rightfully belongs to this land.

General view of the Center of Islamic Civilization

Hall of Glory at the Center of Islamic Civilization

Hall of the Holy Qur’an

Library of the Center of Islamic Civilization

In the 16th–17th centuries, the historian Mutribi Samarqandi, writing about the remarkable achievements of Abdullah Khan a bright representative of the Shaybanid dynasty and the last ruler of Turan cites the Khan’s confession: “...Amir Alisher, while serving Sultan Husayn Mirza, left behind a thousand charitable works. We are khans if we do not bring the number of our constructions to ten thousand, then we have been calling ourselves rulers in vain”.

This shows that every great leader with a noble heart viewed building and creating as the pledge of their own immortality. Yet only a few among them have managed to leave an indelible mark. It is only those initiatives rooted in enlightenment, art, and culture those that drew from these great rivers that have stood the test of time. We have already mentioned this in the examples of the First and Second Renaissances in our own history.

The idea put forward by Shavkat Mirziyoyev is truly unique for its global and universal significance. For example, when you study the activities of this Center, you notice not an attempt to “become a submissive servant of history” as in times past, but rather an eagerness to transform the heritage and traditions of the past by linking them with the present harmonizing history and the future to create a bright horizon.

It is not far-fetched to imagine that the visits of hundreds of prominent scholars from around the world to this Center to engage in creativity and research may give rise to great breakthroughs and even miracles. History provides many examples of this. For instance, not everyone knows the story of how the world-famous opera Aida or the Statue of Liberty in the United States came into being.

In 1869, the ruler of Egypt, Ismail Pasha, commissioned the renowned Italian composer Giuseppe Verdi to write a new opera for the opening ceremony of the Suez Canal. That commission became Aida, which premiered at the Cairo Opera House in 1871. In addition, he requested the French sculptor Frédéric Bartholdi to create a statue of an Egyptian woman holding a torch to be installed at the canal’s entrance. However, due to the high cost, the project was not realized for its original purpose. Later, the famous sculptor used this very design as the basis for what would become the Statue of Liberty.

Overall, our capital Tashkent has never needed praise. This city, with its history stretching far back into antiquity, was mentioned by our great ancestors Abu Rayhan Beruni, al-Khwarizmi, Mahmud al-Kashgari, and even the Greek scholar Claudius Ptolemy (2nd century CE) in his Geography. Throughout the ages, when one said “Tashkent,” the image of the “old city” immediately came to mind. But what happened to this very part of the city the cultural orbit of ancient Shosh in the last hundred years, what kind of urban development took place here?

If you dig into history, you will find that in the 1980s of the last century, during the Soviet period, the “Chorsu” market was built as a gift of Soviet modernism, and during the years of independence, the Hast-Imam complex was restored, followed by the construction of the Zarqaynar Fashion House nearby. Yet, this corner of the city had always been part of the cultural heart of ancient Shosh...

Today, however, set aside some time and visit the “old city” and see the miracle for yourself. If you don’t feel as if you’ve stepped into history, if your imagination does not start a dialogue with the distant past, I will be surprised. In particular, the Qorasaroy street leading to the main entrance of the Center will completely captivate you. To see such transformations accomplished in such a short time honestly, it defies imagination.

I myself once served as the chief executive of several districts of the capital. In those times, it could take years just to get a single sewage line operational, and we would search for months just to find an excavator for repairs. These changes today seem like a dream, like a fairy tale...

I am convinced that the Center of Islamic Civilization will not only revive the spiritual history of the old city but will also transform Tashkent into a cultural hub of our region on par with Samarkand and Bukhara.

There is a famous saying by a Russian writer: “If a gun is hanging on the wall in a play, it must go off by the final act!” Although this refers to theater, its logic can also apply to our current situation. If I do not now explain why I chose such a striking title for this article and how this feeling arose in my heart, then the written text would lose its logic. So let me say it.

Having witnessed this history open before my eyes having become acquainted with the Center of Islamic Civilization two regrets passed through my heart.

First, that despite having such a great history, we were unable to show it to the world. And second, that while our cultural treasures capable of enchanting humanity were scattered across the globe, we never thought to gather them in one place and proudly present them as creations of our own ancestors.

And yet, even after the darkness of the Soviet period had been lifted, and after the era of Sharof Rashidov, when there was at least some breathing space for national issues, how many leaders came to power in this country? Why did we not begin this work even in the years of independence? Why? Why? Why?.. Was it because we had no money? But wealth has not suddenly fallen on us from the sky today. Our cotton, our gold, our gas they have always been here, the same as before. Then why did we not do these things earlier? What were we afraid of?

Naturally, such thoughts create a sense of guilt before history and the pure spirits of our ancestors. The wasted time, the indifference, the neglect of our great history and culture all cause, as I said above, an ache to stir in the heart...

But this ancient world is full of wisdom. Sometimes an unexpected and extraordinary event can wash away sorrow and grief, illuminating not only your heart but the entire world. In this sense, if we take Shavkat Mirziyoyev’s boundless love for the nation and the homeland, his devotion to his filial duty before his own people, as the very blessing of fate that washes away the mistakes of yesterday and the sorrows in people’s hearts we would surely be right.

Qudratilla Rafiqov

Political Scientist

Most read

Over 100 experts from more than 20 countries of the world are in Tashkent!

President of Serbia Aleksandar Vučić visited the Islamic Civilization Center in Uzbekistan

The Center for Islamic Civilization – a global platform leading towards enlightenment