A ladder placed upon the mysterious sky

At various periods in our country’s history, world-renowned civilizations, vast empires, admirable cities, and priceless architectural monuments have emerged. In particular, the unparalleled examples of cultural heritage created by our great ancestors have left an indelible mark on human history. The scientific, historical, and literary works they produced are today preserved in various parts of the world in foreign collections, foundations, libraries, and museums.

At various periods in our country’s history, world-renowned civilizations, vast empires, admirable cities, and priceless architectural monuments have emerged. In particular, the unparalleled examples of cultural heritage created by our great ancestors have left an indelible mark on human history. The scientific, historical, and literary works they produced are today preserved in various parts of the world in foreign collections, foundations, libraries, and museums.

Filling the magnificent building of the Center of Islamic Civilization in Uzbekistan with high-quality and meaningful content requires a special sense of responsibility from each of us. Over the eight years since the Center was established, a large scholarly and creative team of experienced and knowledgeable scholars has been at work. During this time, more than 800 scientific and innovative projects dedicated to the study of our great scholars’ heritage have been developed. Among them, the scholarly legacy of the great Timurid ruler Muhammad Taraghay Mirzo Ulugh Beg (1394–1449) holds a special place.

Mirzo Ulugh Beg is considered one of the founders of the Second Renaissance that took place in the lands of Movarounnahr. During his nearly forty-year reign, science, culture, and architecture flourished in our homeland. Madrasas were built in Samarkand, Bukhara, and Ghijduvan. In particular, the madrasa at Registan Square, inaugurated in September 1420, could easily compete with the world’s earliest universities. In Samarkand, one of the largest scientific institutions in the East the observatory was erected.

Mirzo Ulugh Beg himself, in his free time from governing the state, taught students, observed celestial bodies, and engaged in historical and literary works.

Mir Alisher Navoi, in his Majolis un-Nafā’is, also spoke about Mirzo Ulugh Beg’s outstanding poetic talent and provided examples of his poetry.

During Ulugh Beg’s era, classical Uzbek literature also flourished. Under his reign, Uzbek poets such as Lutfiy, Sakkokiy, Atoiy, Amiriy, and Gadoiy created their works. In the same period, works in the Uzbek language such as Gul va Navroʻz, Makhzan al-Asrār, Yusuf va Zulaykho, Funūn al-Balāgha, and Nahj al-Farādis were written. Commentaries on the Qur’an were produced, and the works of great thinkers such as Sa’di and Nizami Ganjavi were translated.

The great Uzbek poet Lutfiy wrote the following couplet about Mirzo Ulugh Beg:

Ulugh Bek Khan knows well the words of Lutfiy,

Whose colorful poetry is in no way inferior to Salman’s.

(You can find the original verses in the Uzbek language version)

By Ulugh Beg’s order and with his direct participation, the work Tarikh-i Arba’ Ulus (“History of the Four Uluses”) was written, which is considered one of the rarest sources for the study of Turkic peoples’ history.

Under Mirzo Ulugh Beg’s leadership, observations made at the observatory led, in 1437, to the creation of the Zij-i Jadidi Kuragoniy. This work testifies that the science of astronomy in our land began to develop very early. In it, the positions of 1,018 stars in the ecliptic system are presented based on precise calculations.

Under Mirzo Ulugh Beg’s leadership, observations made at the observatory led, in 1437, to the creation of the Zij-i Jadidi Kuragoniy. This work testifies that the science of astronomy in our land began to develop very early. In it, the positions of 1,018 stars in the ecliptic system are presented based on precise calculations.

The question of whether the Zij was written personally by Mirzo Ulugh Beg or by others has not yet been fully settled. However, in the introduction to the Zij-i Kuragoniy, we can find the following statement:

“Then, the poorest and humblest of the Lord’s servants, and the one who strives most toward Allah among them, Ulugh Beg ibn Shahrukh ibn Timur Kuragon, says thus”.

From this sentence, it is clear that the author of the Zij is indeed Mirzo Ulugh Beg himself. Nevertheless, in creating the work, Ulugh Beg also benefited from the scientific views and contributions of many scholars. In the preface, it is noted that Qazi Zada Rumi, Mavlono Salah al-Din Musa, Ghiyath al-Din Jamshid, and Ali Qushchi provided close assistance in this great endeavor.

From the information recorded in the work, we learn that Qazi Zada Rumi was Ulugh Beg’s teacher and took part in the creation of the Zij. There are differing scholarly views about Jamshid al-Kashi, noting that he came to Samarkand in 1416, died soon after the observatory’s observations began, but translated the theoretical section of the Zij into Arabic.

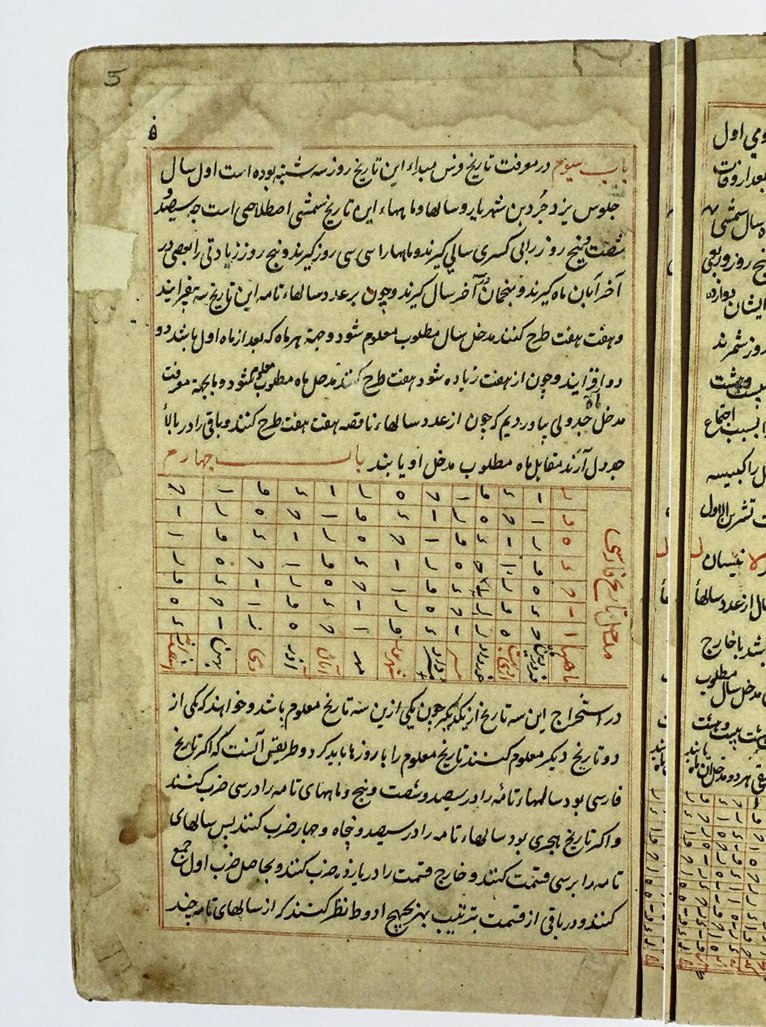

The Zij consists of a preface and an astronomical table compiled in 1437, which precisely identifies the positions and locations of 1,018 fixed stars. The first chapter, titled “Knowledge of History and Chronology”, is devoted to systems of year reckoning and calendar matters. The work compares the Hijri, Syriac, Greek, Jalali, Persian, Turkic, Chinese, and Uighur calendars.

The second chapter of the work, titled “Times and Related Matters,” contains mathematical tables (sines and tangents). The third chapter discusses spherical astronomy (the Sun, the Moon, and the planets in the cosmos), with the main astronomical tables presented in this section.

The fourth chapter of the Zij, called “The Constant Motion of the Stars,” is devoted primarily to astronomy. Ulugh Beg gives the measurement of the inclination angle of the ecliptic (the Sun’s apparent path) relative to the celestial equator. In his study of the cosmos, Mirzo Ulugh Beg employed methods such as observation, experimentation, direct inspection, demonstration, comparison, induction, and deduction.

The Zij was first given scholarly and philosophical commentary by Ali Qushchi of the Samarkand madrasa, followed later by Miram Chalabi and Husayn Birjandi. After the death of Shahrukh, the tragic assassination of Mirzo Ulugh Beg, and the internal conflicts among the Timurids, the leading scholars of Movarounnahr dispersed across the Eastern lands.

Along with their own scientific achievements, these scholars also carried with them original copies of the Zij. For example, in 1473, Ali Qushchi traveled to Turkey, where he established an observatory and played a key role in spreading the Zij throughout the Near East, Middle East, Turkey, and Europe. Today, around 120 Persian and Arabic manuscript copies of the Zij are preserved in libraries around the world.

No other medieval work on mathematics and astronomy achieved the same fame as the Zij. It was studied and commented upon throughout much of the Islamic world. As noted by the eminent scholar B.A. Rosenfeld, at various times scholars such as Muhammad ibn Abul Fath al-Sufi al-Misri, Abulqadir ibn Ruyani Lahiji, Miram Chalabi, Abdulali Birjandi, and Ghiyath al-Din Shirazi wrote commentaries on the Zij.

The Mughal rulers, continuing the traditions of the Samarkand scholars, gathered scientists around them and pursued research in astronomy and mathematics. For instance, during the reign of Shah Jahan, Farid al-Din Mas’ud al-Dehlawi (16th–17th centuries), who worked in Lahore and Delhi, wrote an astronomical treatise titled Zij-i Shah Jahani, in which much of the scientific data and tables were taken directly from Ulugh Beg’s Zij. In addition, Sawai Jai Singh used Ulugh Beg’s Zij as a source in compiling his Zij-i Muhammad Shahi.

Western European peoples and countries were already aware of Amir Temur, the Timurid state, and especially Mirzo Ulugh Beg as early as the 15th century. The Zij also had a considerable influence on the science of Western Europe.

It is believed by some scholars that the construction of the Greenwich Observatory in the southeast of London in 1675, initiated by King Charles II (1630–1685), may have been inspired, at least in part, by the school of Mirzo Ulugh Beg and his famous Zij-i Jadid-i Kuragoniy.

There are two undeniable pieces of evidence to support this view. The first is an astrolabe from the school of Mirzo Ulugh Beg preserved at the Museum of the History of Science in Oxford. The second is a manuscript of the Zij-i Jadid-i Kuragoniy held at the Bodleian Library in the same city.

According to historical records, this manuscript was taken from Samarkand to Istanbul in 1473 by Ali Qushchi, Mirzo Ulugh Beg’s loyal disciple. Ali Qushchi served at the court of Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror, producing works in astronomy, mathematics, logic, linguistics, and other fields. It is likely that, along with numerous works and the instruments used in the Samarkand observatory, he also brought this manuscript to Istanbul.

The Latin notes found in the margins of the manuscript belong to the English scholar John Greaves (1602–1652). Greaves acquired the work in Istanbul in 1638. In April of that year, he met the English merchant and consul Peter White in the Ottoman capital. With White’s assistance, Greaves obtained manuscripts brought from Samarkand by Ali Qushchi, as well as astronomical instruments, and returned to London. Among these were Ptolemy’s Almagest with commentary, Abu’l-Rahman al-Sufi’s Book of the Constellations of the fixed stars, Mirzo Ulugh Beg’s Zij-i Jadid-i Kuragoniy, and an Eastern-style astrolabe.

Later, al-Sufi’s commentary on the Almagest for reasons unknown ended up in France, where it is now kept at the National Library of France. John Greaves had an excellent command of Persian and even wrote a textbook for learning it. Because of this, he studied the Zij-i Kuragoniy in depth and left his notes in its margins. Using the astrolabe he had brought, he investigated the movements of celestial bodies.

In the first part of the work, Greaves became acquainted with the Eastern calendars and carefully studied the Earth’s orbit around the Sun. The calendar in Ulugh Beg’s work, based on his calculation of the average length of the year, proved to be more accurate and precise than the Julian calendar then in use in Europe. Later, on the basis of Ulugh Beg’s work, he petitioned the government to reform the Julian calendar in use in Europe and to introduce a new calendar. However, due to the ongoing English Civil War, the reform was postponed, and it was not implemented until a century after his death.

In 1648, John Greaves published in Latin the table of 98 stars from the Zij-i Kuragoniy. In the same year, he also published the geographical table from the Zij. In 1650, he translated the first part of the Zij into Latin and had it printed. In the final months of his life, he even managed to republish these translations. At that time, these works were thoroughly studied at the universities and scientific centers of Oxford, Cambridge, and London.

John Greaves died in 1652 at the age of fifty. He bequeathed the manuscripts and instruments he had brought from Istanbul to Savile College in Oxford. Later, Oxford scholars used these works and instruments to carry out new research in astronomy. For example, Thomas Hyde (1636–1703), a professor at Oxford University, published in 1665 the table of fixed stars from the Zij in both Persian and Latin.

These works undoubtedly gave a strong impetus to the development of astronomy in England. In 1675, Oxford-trained astronomers such as Robert Hooke and John Christopher were involved, by order of King Charles II, in building an observatory near London. Once completed, the observatory appointed another famous English astronomer, John Flamsteed, as its first Astronomer Royal. Initially intended to determine coordinates for navigators, the observatory was built precisely on the location identified as the zero meridian. Later, a special clock was installed in the main building to determine the exact time, which led to the internationally renowned term “Greenwich Mean Time”.

In conclusion, the roots of such discoveries and scientific terms of global significance can be traced directly to the intellect and genius of our ancestors. Indeed, from the adoption of a new calendar in Britain to the construction of the famous Greenwich Observatory and the concept of Greenwich Mean Time, Mirzo Ulugh Beg’s contributions are undeniably present.

Regarding the Zij-i Kuragoniy, which brought about a major shift in the history of world science, Uzbekistan’s Hero and People’s Poet Erkin Vohidov wrote:

Mirzo Ulugh Beg Kuragoniy compiled his tables,

And placed the first ladder upon the mysterious dome of the sky…

(You can find the original verses in the Uzbek language version)

In 2023, through the initiative of the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Uzbekistan and the Samarkand International University of Technology, and with the sponsorship of Eriell Group International Oilfield Services, the Zij-i Jadid-i Kuragoniy was published in Uzbek, Russian, English, and Chinese using modern printing technology. At present, the Center of Islamic Civilization in Uzbekistan is preparing for a new edition of this work.

Rustam Jabborov

P/S: The article may be used provided that the official website of the Center is cited as the source.

Most read

Over 100 experts from more than 20 countries of the world are in Tashkent!

President of Serbia Aleksandar Vučić visited the Islamic Civilization Center in Uzbekistan

The Center for Islamic Civilization – a global platform leading towards enlightenment